It turns out, ticks are HARD to kill with frost. They have to go down to TEN DEGREES Fahrenheit – and stay there for a couple DAYS before they perish. Fact is, most of them never get that cold, can get into the dirt and leaf litter in the forest or better: Onto a warm host and make it through.

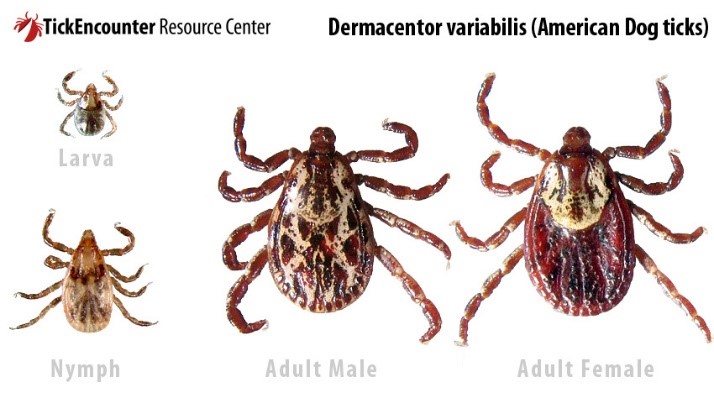

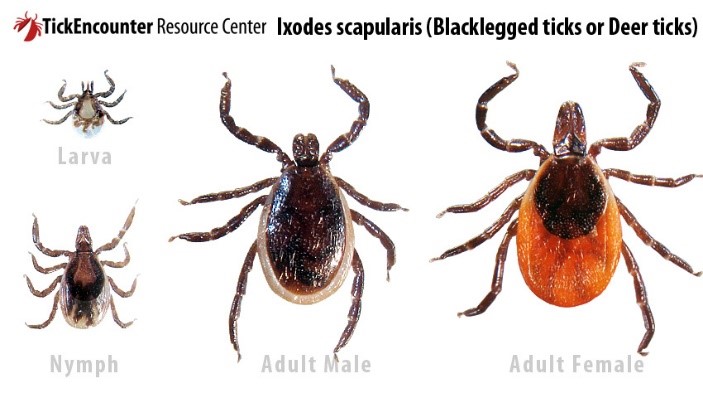

Something I didn’t know: It’s not the great big obvious ADULT tick that spreads Lyme. It’s the “nymph” phase, see picture below. And it’s not the American Dog Tick as much as the Black-Legged DEER tick that carries and spreads Lyme Disease.

From: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/transmission/index.html

Ticks not known to transmit Lyme disease include Lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum), the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni), and the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus).

Here’s other stuff I found (References cited):

WHAT HAPPENS TO TICKS IN THE WINTER?

Ticks are more active during certain times of the year depending on the species and region. Spring, summer and fall can be dangerous times for anyone who enjoys nature. But you may find yourself wondering: Are there ticks in the winter? What happens to ticks in winter weather may surprise you.

DO TICKS DIE IN THE WINTER?

No. Ticks survive the winter in a variety of ways, but do not go away just because it is cold. Depending on the species – and stage in their life cycle – ticks survive the winter months by going dormant or latching onto a host. Ticks hide in the leaf litter present in the wooded or brushy areas they tend to populate. When snow falls, it only serves to insulate the dormant ticks, which are protected by the layer of debris. Or, in the case of soft-shell ticks, they survive by staying underground in burrows or dens.

Can You See the Difference Between Tick Species?

ARE TICKS OUT IN THE WINTER?

It depends. Some types of ticks can be active if the temperature is above 45 degrees Fahrenheit and the ground is not wet or icy. The American dog tick and lone star tick are not typically active during the fall and winter months. Blacklegged ticks, which carry Lyme disease, remain active as long as the temperature is above freezing. The adults look for food right around the first frost. Additionally, the winter tick, which hatches in late summer as temperatures begin to decrease, is active during cooler months. This tick is typically found on moose, and sometimes deer, in the Northeastern part of the country. These ticks are different from other species, because they will spend their entire lives on one host. Winter tick eggs hatch on the ground in August and September. Larvae seek out a host between September and November. Those that find a host will overwinter on it, holding onto its hair when they are not feeding. Those that cannot find a host will likely die. Females will remain on a host until the end of winter or start of spring. Then they drop into the leaf litter, where they will lay up to 3,000 eggs before dying.

Special thanks to the folks at Terminix

https://www.terminix.com/pest-control/ticks/facts/ticks-in-winter/

More, this is from: https://www.colonialpest.com/where-do-ticks-go-in-the-winter/

Blacklegged ticks decrease activity only when the temperature drops below 35 degrees F. or the ground is snow-covered, but they quickly recover when things warm up just a little. For freezing temperatures to actually kill ticks, there must be a sustained number of days below 10 degrees F. This happens less often as our winters, in general, are warmer than they used to be. Even then, any tick that has attached to a deer will be kept warm by the animal’s body heat and will easily survive a cold snap.

LYME DISEASE TICKS ARE A THREAT YEAR-ROUND

What this means is that you can’t really let down your guard when it comes to ticks and the possibility of tick-transmitted diseases. You can take a small breath though because, in the Northeast, the risk of Lyme disease is lowest from late December to late March. This is due not so much to the weather as it is to the complicated life cycle of the blacklegged tick. The nymphal stage of the tick is responsible for most transmitted cases of Lyme disease, but by late fall the nymphs have molted into adult ticks to spend the winter.

.

.

.